I just read Jackson Cuidon’s less than stellar review of the animated movie Turbo. His review follows others that expected more from Dreamworks Studios in their battle with Pixar for animated movie superiority. However Cuidon’s review remains isolated from the general entertainment pontifications in that he reviews TV and movies for Christianity Today. One would expect (or at least I did) an attempt to connect Christianity to culture (isn’t that what the title of the website/magazine implies?). Generally his review of the movie comforted parents about the content, while raising the perceived problem “that Turbo never earns anything he achieves.” He is referring the fact that the nitrous oxide ingested by Turbo, enabled him to “achieve” a victory he did not earn. This critique is fair from a western capitalist perspective, but weak from a gospel perspective. Cuidon completely missed a gospel inculturated opportunity. Instead of asserting that Turbo never earns anything he achieves, might we ask how can a snail do the impossible? Something outside of him and not part of him enabled him to do great things. Isn’t this a gospel moment? We are in many ways like Turbo. Apart from the enabling work of the gospel, we cannot attain anything. We can’t even get to the racetrack much less compete in the race. The gospel enlivens us and enables us to not only compete, but win. The work of the gospel through the power of the Holy Spirit, enables us accomplish things thought not possible. Paul says, “Be energetic in your life of salvation, reverent and sensitive before God. That energy is God’s energy, an energy deep within you, God himself willing and working at what will give him the most pleasure” (Phil 2:12b-13, The Message). This perspective of Turbo refreshes me even if it does not present the best plot line or contain the latest digital wow. It reminds me, even in the simple pleasures we enjoy with our children, that God enables us to achieve what we did not earn.

I just read Jackson Cuidon’s less than stellar review of the animated movie Turbo. His review follows others that expected more from Dreamworks Studios in their battle with Pixar for animated movie superiority. However Cuidon’s review remains isolated from the general entertainment pontifications in that he reviews TV and movies for Christianity Today. One would expect (or at least I did) an attempt to connect Christianity to culture (isn’t that what the title of the website/magazine implies?). Generally his review of the movie comforted parents about the content, while raising the perceived problem “that Turbo never earns anything he achieves.” He is referring the fact that the nitrous oxide ingested by Turbo, enabled him to “achieve” a victory he did not earn. This critique is fair from a western capitalist perspective, but weak from a gospel perspective. Cuidon completely missed a gospel inculturated opportunity. Instead of asserting that Turbo never earns anything he achieves, might we ask how can a snail do the impossible? Something outside of him and not part of him enabled him to do great things. Isn’t this a gospel moment? We are in many ways like Turbo. Apart from the enabling work of the gospel, we cannot attain anything. We can’t even get to the racetrack much less compete in the race. The gospel enlivens us and enables us to not only compete, but win. The work of the gospel through the power of the Holy Spirit, enables us accomplish things thought not possible. Paul says, “Be energetic in your life of salvation, reverent and sensitive before God. That energy is God’s energy, an energy deep within you, God himself willing and working at what will give him the most pleasure” (Phil 2:12b-13, The Message). This perspective of Turbo refreshes me even if it does not present the best plot line or contain the latest digital wow. It reminds me, even in the simple pleasures we enjoy with our children, that God enables us to achieve what we did not earn.

Category Archives: Gospel and Film

Turbo Gospel

Comments Off on Turbo Gospel

Filed under Aesthetics, Gospel and Film, Racing

A “Just” view of the world

.

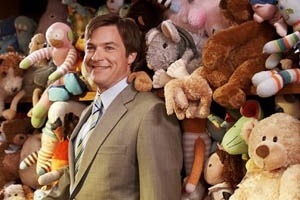

During Christmas break I watched Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (2007) with my middle son. In the movie Mr. Magorium [Dustin Hoffman] hires an accountant whom he affectionately calls “Mutant” [Jason Bateman]. A particular conversation between Molly Mahoney [Natalie Portman] intrigued me. As “Mutant” attempts to make sense of the activities inside the toy store, he inquires of Mahoney as to the happenings in store.

During Christmas break I watched Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (2007) with my middle son. In the movie Mr. Magorium [Dustin Hoffman] hires an accountant whom he affectionately calls “Mutant” [Jason Bateman]. A particular conversation between Molly Mahoney [Natalie Portman] intrigued me. As “Mutant” attempts to make sense of the activities inside the toy store, he inquires of Mahoney as to the happenings in store.

Molly Mahoney: It’s a magical toy toy store

Mutant: It’s just a toy store

Mahoney: You’re a “just guy”, you look at the world and say, it’s just a toy store. A guy that walks around no matter what it is just what it is nothing more.

This conversation made me think about God’s wonderful work in this world, his miraculous activities among us everyday, the little things often ignored that wouldn’t be without the sustaining work of our great God. Many times our response to such activities is, it’s just a sunrise, it’s just another birth, it’s just another migrating bird, or its just another…. Molly Mahoney recounts, “In every corner of this store, the miraculous happened every minute of every day.” Just like Molly Mahoney, I want to be more than a “just guy,” I want to be the guy that looks and sees God’s miraculous in the mundane, then celebrates them. In the end, there is no “just” because God’s interest in his creation is in itself a miracle indeed. His interest is not more brightly seen than in this season of celebration of the birth of our Christ.

Comments Off on A “Just” view of the world

Filed under Gospel and Film, Spirituality, Theology

Abbot Suger and the Doors of St. Denis: Should Churches be Aesthetically Pleasing?

Through construction of his new church at St. Denis in 1122, Abbot Suger is commonly thought as the catalyst for Gothic church architecture. Deeply criticized for the extravagance of the church, he ignored the critics and completed the project. He sought to employ architectural methods that mirrored the glory of God and sense of awe in religious experience. When completed he had these words inscribed on the church doors,

‘Whoever thou art, if thou meekest to extol the glory of these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and the expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.

Bright is the noble work; but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights,

To the True Light where Christ is the true door.

In what manner it be inherent in this world the golden door defines:

The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material

And, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.’And on the lintel:

‘Receive, O stern judge, the prayers of Thy Suger;

Grant that I be mercifully numbered among Thy own sheep.’[1]

I really admire the church architecture of the past and think we are missing something when we construct churches that mirror society instead of God. Many churches today look like over sized houses or undersized big-box retail stores. Very little thought is placed on purposeful aesthetics. Purposeful aesthetics in a divine context aspires to tell something about God through architecture, art, design, and layout. Few churches take this into account when constructing a new facility or revamping the old one. Most spend their money on volume space over ornate interest. Granted, concern for utility must be addressed; it would be pointless to have a architecturally beautiful church that proclaims purposeful aesthetics that is unusable. However, most do not even entertain how their church architecture could proclaim divine beauty or tell the glory of God. So to rescue myself from the hypothetical, let me suggest a few ways that any church could begin this progression. First, incorporate art into your church. I am not talking about those cheesy (sorry if you like them) pictures of Jesus that portray him as a 1960’s hippee. I am talking about images that would be found in an art gallery or museum– images that portray the divine and divine acts. Most churches have very little art in them, why not incorporate an art gallery the highlights Christian artists? Second, think theologically when arranging your building. Recently while in Louisville, I visited two labyrinths, one at the Louisville Seminary and the other at Church of the Epiphany. Walking through these allowed me to experience many things, but the most apparent thing was how it mirrored our journey through life. Sometimes I was really close to the center or the end, but still had a long way to go if I followed the path. This created a bit of anxiety and longing to complete the journey through the labyrinth. I am not suggesting everyone build a labyrinth (although they would make a great addition!). There are other ways to create the same idea. One might be constructing the entry to your church that give all who enter a journey through the entry a feeling of anticipation that ultimately results in them entering the worship area where they encounter images of the cross or other images that tell them Christ is with them. Another might be in arranging the worship area so that the focal point is centralized (most churches have many more than one). The ways to make a church aesthetically pleasing with a purpose is endless, but yet few consider it even a profitable discussion. In this age of visual consumption, purposeful aesthetics must be part of the conversation.

[1] Thiessen, Gesa Elsbeth. Theological Aesthetics: A Reader. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub, 2005, 115.

Comments Off on Abbot Suger and the Doors of St. Denis: Should Churches be Aesthetically Pleasing?

Filed under Aesthetics, Current Church Trends, Gospel and Film, Spirituality

Tudor Morality Plays and Modern Cinema: Forgiveness, Repentance, and the Four Last Things

This is a series of posts on Tudor Morality Plays and Modern Cinema (Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death; Central Character, Ritual in morality plays and Repo Men; Forgiveness of Sins). It might benefit one to read the previous posts prior to this one.

Forgiveness sins are a vital component of the morality play. Potter suggests, “In demonstrating first the necessity for repentance, and then the fact of its efficacy, the morality playwright seeks the participation of his audience in a ritual verification of the whole concept of the forgiveness of sins.”[1] The forgiveness of sins must first begin with the introduction of mankind into the state of sin. In the plays man found immediate pleasure in sin and the act of sinning is virtually unavoidable. Therefore the state of innocence previous to sin understated or portrayed as theoretical.[2] During the fall from innocence, “the sexual seduction of Mankind into sin is dramatized, either in a literal seduction scene (as with Mankind and Lechery in Perseverance) or by inference, with lemans, wenches, and brothels indicated just offstage.”[3]

Repo Man also delivered the vice of greed sensually. The immediate pleasure of sin revealed itself in the acts of greed. For Remy, the pleasures were found in a dream of house in the suburbs, wife, and child. Remy initially and Jake throughout the film, find pleasure in identification with their profession. Both liked being respected and feared as repo men. A scene where they scan a large man (which enables them to identify transplanted part information) and bet if he is overdue best illustrates this. When the scan reveals the man has two days left, they let him know they will be calling on him in two days.[4] Throughout the film, both choose to enter through the front door of the Union building, at which time Frank admonished them because they are scaring the customers.[5] Literally, Repo Men has it share of sexuality throughout the film that supports the vice of greed. The first customer encountered by Remy in the film has brought home a prostitute for the night.[6] This suggests his greed for all of life overrules responsibility in paying his debts. Remy’s paperwork contract for his heart is delivered to him in the workplace by an exotic dancer.[7] Throughout film the job and the life that the job provides identified with sensual pleasures.

Once man has sinned in the play there comes a call to repentance. No two calls to repentance in morality plays are identical however in all of them repentance is the climatic theatrical event. In most of the medieval plays an attempt is made to dramatize this transformation in the specific terms of the sacrament of penance.[8] Potter concludes, “Thus the traditional morality play is not a battle between virtues and vices, but a didactic ritual drama about the forgiveness of sins. Its theatrical intentions are to imitate and evoke that forgiveness.”[9]

Remy explicitly claimed in narration that he was not seeking forgiveness for all the wrongs he had done. However when contemplating his role with Beth, he mused that he is saving himself along with her. In a sense when he reclaimed all the organs, from Beth and himself he was getting forgiveness for his actions. The question might remain, who is granting the forgiveness. On one hand, it could be Union as it scanned the parts back into inventory. However, on the other hand, it could be Jake. Since the pink door scene is a neural implant and not reality, it is Jake granting forgiveness to Remy by allowing the neural memory to exist.

Highlight on forgiveness does not suggest the vices and virtues are not significant in morality plays. In a real sense virtues and vices play a role in bring mankind to the point of repentance. This contest between Virtue and Vice is ultimately for the possession of man’s soul. Because it battled for man’s soul, it focused on what Holzknecht calls “the Four Last Things.” He suggests that, “Death, Judgment, the pains of Purgatory or Hell, and, alternately, the joys of Heaven, which were to be had if a man remembered the first three and refrained from sin or repented in time.”[10] In interacting with the virtues and vices the audience is presented with the choice of life in repentance or death in rejection of faith.

This focus on the four last things was a common topic outside morality plays which allowed for an easy transition into the plays. The cult of death was prominent in England and “traditional literary forms were the treatise on the ‘art of dying well,’ including detailed instructions and formulas for preparing for the inevitable hour; and ‘the four last things,’ a sounding of the meaning of death, judgment, heaven, and hell.”[11]

The entire story of Repo Men reacted to the art of dying well. Clients came to the Union company for organs and are willing to giving anything to avoid death. However, for those who financed their organs, it will still lead to death as they can never afford the financial terms. Neither Frank nor Jake have prepared for the “inevitable hour.” Frank, who is without any compassion whatsoever, dies in Remy’s neural dream without redemption. In reality, he continued to exist as a cold-hearted manager looking to keep sales up for Union company. Jake found complete redemption and is ready for the inevitable hour, at least in Remy’s neural dream. However, even reality, it appeared he has made progress toward that goal. He paid the cost Remy’s transplant debt and provided for Remy’s future well being. These acts signified that, at some level, he gained awareness that greed must be restrained. At the end of the movie, Beth remained alive, with her fate in the hands of Jake. He must make of choice to recover her overdue organs or set her free. Jake’s decision is not revealed in the movie. To Beth, in the end it does not appear to matter, she has found redemption through her relationship with Remy. Throughout the film Remy took care of her in spite of her faults, caring for her over himself. Beth too gave of herself to Remy. Both had freed themselves from greed ready to give their lives for each other. Remy, in both reality and neurologically though the implant, found redemption and clearly prepared for the final hour. In doing so, he avoided (at least temporarily) death and gained heaven (neurologically).

[1] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 47-48.

[2] Ibid., 48.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 12:56.

[5] Ibid., 9:45.

[6] Ibid., 2:21.

[7] Ibid., 38:40.

[8] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 49.

[9] Ibid., 57.

[10] Karl J. Holzknecht, The Backgrounds of Shakespeare’s Plays (New York: American Book Co., 1950), 322-323.

[11] Williams, The Drama of Medieval England, 147.

Comments Off on Tudor Morality Plays and Modern Cinema: Forgiveness, Repentance, and the Four Last Things

Filed under Aesthetics, Gospel and Film, Philosophy

Tudor Morality Plays in Modern Cinema: Forgiveness of Sins

[see previous posts on Tudor Morality Plays: pt 1, pt 2, pt 3]

The morality plays have frequently been mistaken for naïve treatises on virtue. They are in fact the call to a specific religious act.[1] In the thirteenth century, the friars preached on penance and virtue and vices to the general populace.[2] Potter suggests that, “The mixture of doctrine and realism in the morality play has its origins in this preaching tradition, and the immediate sources of allegory in the morality play are almost invariably found in medieval sermon literature.”[3] Throughout this period, preachers devoted themselves to “to moving their listeners to take up the penitential process of contrition, confession, and satisfaction to gain forgiveness of their sins.”[4] This theme of penitence and forgiveness dominates morality plays.

After receiving his heart transplant, Remy displayed penitence and sought forgiveness in several scenes. First, his sorrow for his past actions is recognizable in his acknowledgment of the humanness transplant repossession victims. He realized they have a name and family. Even in the underground, he confronted a person that scavenged dead bodies for transplant organs. Discussing what remains of dead bodies, he in disgust asserts, “What do you do with your clients when you are done with them, chop them up for dog meat?[5] Second, Remy sought forgiveness through the rescue of Beth and ultimately himself. In bringing her on the road to redemption, he is bringing himself to redemption. He found his forgiveness (though in the cautionary tale he admits not fully) through the process of redeeming Beth from the Union in the final scene.

A significant connection existed between the morality plays and the concept of the seven deadly sins.[6] Most did not entertain all seven, earlier moral plays seemed to center on the examination of one vice in particular, Castle of Perseverance on Avarice, Mankind on sloth, and Pride of Life on pride.[7] The medieval period produced a corresponding set of cardinal virtues, but the traditional seven virtues did not accurately correlate since they were of a different origin.[8] Nuess suggests that, “To supply this lack, medieval homilists prepared a series of lists known as remedia or cures for the seven deadly sins. It is to this tradition that the ‘virtues’ of The Castle of Perseverance belong.”[9] Personified virtues, a central figure or figures that will epitomize the human condition, and the devil as tempter.[10] Therefore, “a fundamental rhetorical separation between the play world and the real world, as players take on the roles of qualities, e.g. Mercy; supematural beings (Good Angel); whole human categories (Fellowship); and human attributes (Lechery).”[11] Players were differentiated on stage through attractiveness and comedy. Wertz explains that, “Vice is far more attractive on the stage than virtue, which appears rather stuffy and dull. The comic, undignified devils of the mystery plays, become the ‘vices’ of the moral play, who degenerate from supernatural demons into riotous clowns.”[12]

Penitence was employed for those transgressors of the seven deadly sins. One instrument of penitence included recitals of the Lord’s Prayer. The prayer retained seven distinct petitions: (1) hallowed by thy name, (2) The kingdom come, (3) Thy will be done, (4) give us daily bread, (5) Forgive us as we forgive, (6) Lead us not into temptation, and (7) Deliver us from evil. Potter explains that,

‘Hallowed be thy name’ is a reminder to resist pride, ‘thy kingdom come’ warns against envy; and so forward through wrath, sloth, avarice, gluttony and lechery. The relevance of the petitions to the sins is sometimes strained (eg., ‘give us … daily bread’ is a remedy for sloth), but these allegorical interpretations of the Lord’s Prayer appear frequently in collections of medieval sermons and other penitential literature.[13]

He continues, “The esoteric remedia of the Paternoster against the deadly sins thus became public knowledge, as part of the educational campaign which sought to implement the institution of the sacrament of penance.”[14] The public preaching of penitence, teaching of the need for forgiveness of the seven deadly sins, and the exhortation of the life of virtues created a natural relationship for implementation of these concepts into morality plays.

Repo Men reveal several vices but the one most prominent is the vice of greed. Prior to the heart transplant, Remy displayed this vice well. In an opening scene, he confronts a transplant for repossession. The person stated he can now pay. Remy responded, “That’s not my department.” He then proceeded to render the customer unconscious to extract the organ.[15] Jake also displayed greed in attempting to keep Remy in the repo department. He put him at risk through sabotaging the defibrillator so that Remy would need a new heart which would put him in need of the income of a repossession agent. Jake asserts, “You thought it was fate? A sort’a cosmic plan to get you right with the world, is that what you thought? …All you had to do is to keep working, you and me doing our thing… I tried to save your life” [by keeping Remy from a sales job].[16] Jake’s greed carried him to extract an overdue organ in a waiting taxi in front of Remy’s house during a barbeque. Jake explains to an apprehensive Remy, “It’s a double commission, I’ll give you half.”[17] The Union corporately is based on greed. The transplant recipients are faced with the decision of death by organ failure or insurmountable debt. A salesperson outlines the terms to potential clients, “Now if you can’t afford the full payment of $618, 429.00, we can offer monthly installments at an APR of 19.6% standard for a generic pancreatic unit.”[18] The general disregard for human life because of greed is the predominate theme of the movie, bodies are ravaged and left to die so that company assets can be recovered and resold to the next victim.

[1] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 16.

[2] H. Leith Spencer, English Preaching in the Late Middle Ages (Oxford [England]; Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, 1993), 145.

[3] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 20.

[4] Larissa Taylor, Preachers and People in the Reformations and Early Modern Period (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2001), 359.

[5] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 1:18:29.

[6] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 21.

[7] Paula Neuss, “The Pardoner’s Tale: An Early Moral Play?,” in Religion in the Poetry and Drama of the Late Middle Ages in England(Cambridge, England: D S Brewer, 1990), 119.

[8] Historically the seven deadly sins are classified as three spiritual sins (Pride, Envy, Wrath) and four corporal sins (Accidia (Sloth), Avaricia/Cupiditas (Greed), Gluttony, Lust. The original seven virtues are classified as three spiritual virtues (Fides (Faith), Spes (Hope), Cartias (Charity) and four cardinal virtues (Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude, Justice). However, these do not directly correspond to one another so the remedial model formed at virtue to cure the vice. Therefore, Pride corresponds to Humility, Envy to Charity, Covetousness to Largess, Anger to Peace, Sloth to Patience, Gluttony to Abstinence, Lechery to Chastity.

[9] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 21.

[10] Robert Potter, “The Ordo Virtutum: Ancestor of the English Moralities?,” in Ordo Virtutum of Hildegard of Bingen(Kalamazoo, Mich: Medieval Inst Pubns, 1992), 32.

[11] Pamela King, “Morality Plays,” in The Cambrige Companion to Medieval English Theater, ed. Richard Beadle(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 241.

[12] Dorothy Wertz, “Conflict Resolution in the Medieval Morality Plays,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 13, no. 4 (1969): 439.

[13] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 22.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 2:44-2:47.

[16] Ibid., 1:23:54-1:24:44.

[17] Ibid., 18:38.

[18] Ibid., 7:54-8:08.

Filed under Aesthetics, Ethics, Gospel and Film, Philosophy

Tudor Morality Plays in Modern Cinema: Ritual in morality plays and Repo Men

This post continues the series on Tudor Morality Plays and their ongoing presence in modern cinema. The earlier posts, entitled Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death, and Central Character can be read in these links. The issue of ritual to morality plays are also present in modern cinema. Throughout the series I have chosen to employ the film Repo Men as representative of modern cinema. If you are unfamiliar with the film, perhaps this article would be more meaningful after reading the plot summary linked above.

This post continues the series on Tudor Morality Plays and their ongoing presence in modern cinema. The earlier posts, entitled Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death, and Central Character can be read in these links. The issue of ritual to morality plays are also present in modern cinema. Throughout the series I have chosen to employ the film Repo Men as representative of modern cinema. If you are unfamiliar with the film, perhaps this article would be more meaningful after reading the plot summary linked above.

Ritual in medieval drama visibly symbolized an invisible ‘spiritual’ action performed in reality.[1] The plays make visible the desired spiritual trait or activity. Through this ritual, “a collective articulation is being celebrated; from past experiences and individual responses, a collective attitude is formulated.”[2] The morality play served the audience by reviewing right attitudes set in a contemporary scenario. Potter explains that, “By rehearsing in an articulated and formal sequence the correct attitudes, ritual causes the truth to ‘come true.’”[3] Ritual then functioned to integrate general truths out of the particulars of human experience. The plays make a connection “between this outer world of events and the inner world of feelings.”[4]

Repo Men followed the sequence of plot development found in morality plays. As stated above, Remy found redemption of sorts through the rescue of Beth from her life of drugs. These truths are further recounted in Remy’s typed cautionary tale. He states,

“So what is it that I am writing? It is not some crappy memoir or even an attempt for apologizing for everything I have done. This is a cautionary tale– A hope that you might learn from my mistakes. ‘Cause in the end, a ‘job is not a job,’ it’s who you are and if you want to change who you are, first, you have to change what you do.”[5]

It is in the details of Remy’s human experience that he is able to draw out particular truths for the audience. The moral of Remy’s tale reflects biblical concepts that one’s acts reflect what their heart desires most.

Origins of the structure of morality plays remain uncertain.[6] However vague the origins it is certain that, “the morality play, an archetypal example of the theater of demonstration, is both didactic (in the sense of teaching Christian doctrine) and ritualistic (in the sense of ‘proving’ it). These interwoven strands of didacticism and ritual together provide the origins of the morality play.”[7] Repo mendemonstrate teaching in Remy’s narrations throughout the movie, calling viewers to take heed of his story and change their ways.

[1] Gordon Kipling, Enter the King: Theatre, Liturgy, and Ritual in the Medieval Civic Triumph (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, 1998), 19.

[2] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 10.

[3] Ibid., 11.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 1:02:38-1:03:17.

[6] See Potter (1975) 12-13. He suggests, “There are indications that at least the structure of the morality play (as distinct from its intellectual substance, which is medieval and Christian) can be traced to similar origins in fertility ritual. The link which connects morality play and ritual is a folk ritual drama known as the mummers’ play. Exactly what the mummers’ play was like in the Middle Ages we cannot be certain, since it is an orally transmitted form (like the ballad) which went officially unnoticed until folklorists began to record it in the eighteenth century.”…“However three facts are abundantly clear: the mummers’ play is an ancient outgrowth of fertility ritual; it existed in some form in medieval times; and it influenced the developing medieval drama.”…“Its central act, a battle of champions to the death, with a miraculous revival, reproduces the ritual battle of winter and summer, the rhythm of death and regeneration, the ritual burial of winter and the resurrection of life” (12). However the similarities between the mummer’s play and morality play should not be overstressed. “Medieval scholars are justifiably cautious about ‘pagan’ myth and ritual, and its supposed dominance in Christian works of literature” (13).

[7] Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition, 16.

Filed under Aesthetics, Ethics, Gospel and Film, Philosophy

Tudor Morality Plays in Modern Cinema: Central Character

An earlier post, entitled Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death, began a series of posts about the relationship between Tudor morality plays and modern cinema. I want to continue that series here addressing the central of lead character’s role in both morality plays and modern cinema. Throughout the series I have chosen to employ the film Repo Men as representative of modern cinema. If you are unfamiliar with the film, perhaps this article would be more meaningful after reading the plot summary linked above.

An earlier post, entitled Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death, began a series of posts about the relationship between Tudor morality plays and modern cinema. I want to continue that series here addressing the central of lead character’s role in both morality plays and modern cinema. Throughout the series I have chosen to employ the film Repo Men as representative of modern cinema. If you are unfamiliar with the film, perhaps this article would be more meaningful after reading the plot summary linked above.

The central figure or series of figures in morality plays define the concept of what it means to be human. Ancillary characters, defined by their function, stand at the service of the plot, which is ritualized, dialectical, and inevitable.[1] The character roles provide for the standard plot arrangement, which necessarily includes that man, exists, he falls, but he is saved. This pattern is repeated in form for every morality play. Unlike the secular life cycle [man lives then dies with no eternal consequence], man is delivered by divine grace to gain salvation and eternal life. The plays remind the audience that “the end of human life is not ‘mere oblivion’ but regeneration: never death, always a rebirth.”[2] The offer of life fulfilled would have significance in the period of history where man found himself ensconced in significant disease, plague, and premature death.[3]

Remy portrays this humanness and the plot of Repo Men follows the arrangement of innocence, fall, and restoration found in morality plays. The two are interrelated in many ways. Remy’s humanness appears early in the film as the opening scenes have him at a typewriter without a shirt composing what he later terms as a cautionary tale.[4] The bareness of Remy, in the way he was famed in the shot at the typewriter, appearing almost naked delivered an image of innocence. However, the content of the typed message (and revealed later in the plot) narrated by Remy display the final movement of a play involving repentance. One way the plot progressed is by counting the time Remy was knocked unconscious. This act marks major milestones in his life. (1) He was knocked unconscious in Army training which enabled to him to qualify for tank duty. This was his first encounter with killing humans. Remy and Jake celebrated at tank rounds obliterated enemy vehicles. (2) While they celebrated in a bar upon return from the war, Remy was knocked unconscious. Remy recounts that “one night the war was over and we were all dressed up and nowhere to go….For us the war never ended it just changed venue”[5] Remy and Jake find a way to continue their killing through legal means with repossession jobs for the Union company. (3) While doing his final repossession before consenting with his wife’s desire for him to move to sales, Remy is knocked unconscious by the sabotaged defibrillator. At this point he received a heart transplant which placed him in the debt of the Union. More importantly, he realized the humanness of his victims. After returning to work, Remy attempted to continue to repossess organs, but cannot complete the task. While sitting in a bar with colleagues that were recounting stories of whimpering victims, Remy recounted to himself, “All I can think about is how that schmuck has a name, and a wife, and kids.”[6] This is an important turn in plot as Remy now begins his journey of redemption. He attempts to reunite with his wife and family but is spurned. This forced him to move in with Jake. (4) Because Remy is unable to repo, he took the sales job, but fell behind on his heart transplant payments. Jake drove him to a target rich area to help him get regain confidence. While there a potential victim knocked him out. When Remy awoke he encountered Beth, whom he heard singing earlier in a bar. He rescued Beth from drugs and ultimately from being repossessed as she had many transplants. Remy narrated, “The thing is I have an artificial heart, she has an artificial everything else; maybe we’re two parts of the same puzzle. Maybe it’s not just her I’m trying to save.”[7] Remy understood that through saving Beth he is saving him self. (5) The final knock out came by way of Jake in a confrontation with Remy and Beth in the underground. The movie leads the viewer to perceive that all ends well. Remy, Beth, and Jake team up to bring down the Union and escape to the tropics to live happily ever after, but this is a fantasy all in Remy’s neural mind plant. When Jake knocked out Remy in the underground, Remy suffered brain damage and does not regain consciousness. Instead he is implanted with a “M5 Neural Net” device that allows victims of brain damage to live out the rest of their natural lives as Frank advertised– “where they are always happy, always content, and always taken care of.”[8]Therefore Remy portrayed the major movements of the morality play: innocence, fall, and redemption. Each time Remy regained consciousness, he entered a new movement, ultimately entering “heaven” with the M5 Neural Net device supplied by Jake.

[1] Robert A. Potter, The English Morality Play: Origins, History, and Influence of a Dramatic Tradition (London; Boston: Routledge & K. Paul, 1975), 7.

[2] Ibid., 10.

[3] Colin Platt, Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology from the Conquest to 1600 A.D (London; New York: Routledge, 1994), 137.

[4] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 1:23-1:57:46.

[5] Ibid., 32:05-32:11.

[6] Ibid., 40:49-41:43.

[7] Ibid., 57:35-57:56.

[8] Ibid., 1:52:47-1:52:59.

Filed under Aesthetics, Community, Gospel and Film, Philosophy, Spirituality

Tudor Morality Plays in modern cinema: Set, Costumes, and Dance of Death

A set diagram from the 15th century morality play "Castle of Perseverance."

Medieval period morality plays arose out a desire to educate the common person about moral values based on biblical principles. The basic concepts of morality plays are clearly evident in Elizabethan plays through the time of Shakespeare and remain evident in modern drama even today. However, what about their influence on motion pictures? Can the basic concepts of medieval morality plays be found in film too? The Bible greatly influenced western culture. In the arts by way of the morality play, some of this biblical legacy remains influential in modern day motion pictures. Characteristics of the content found in morality plays are evident in motion pictures such as Repo Men. This post is intended to introduce morality plays with following posts comparing them to the cinema movie Repo Men.

The earliest extant morality play is a fragment called, by its modern editors, The Pride of Life. The text is written in the blank spaces of a roll containing the accounts of the canons of Christ Church, Dublin, for the years 1333-46.[1] Morality plays rose out of a need to educate the common man about spiritual issues. This new emphasis on teaching and didacticism, “was the practical result of earlier reforms designed to produce laymen better educated in spiritual matters.”[2] Dorothy Browns suggests that, “The broader concerns in the later moralities were generally those of sins and abuses detrimental to man and society and were not focused specifically on religious dogma.”[3] Morality plays impacted theater long into the Elizabethan age. Williams suggests that, “Morality play dominated the theater, extended and adapted as it was to a variety of purposes, religious controversy, social satire, political propaganda, and even the dramatization of history.”[4]

The extant morality plays are few. While fragments of others remain, the primary morality plays include, The Pride of Life, The Castle of Perseverance, Wisdom (or Mind, Will, and Understanding), Mankind, and Everyman. Only fragments remain from The Pride of Life but its plot is preserved in summary through the speech of the Prolocutor at the beginning of the play. Davidson summarizes that plot as, “The King of Life, assisted by his counselors Strength and Health, is a strongly masculine champion of pride which defies all fear, including that of death.”[5] The Castle of Perseverance “especially stresses the alienation from God and from the ideal life of religious devotion and virtue that occurs when one submits himself (or herself) to the social and political pressures of the time.“[6] Wisdom (also called Mind, Will, and Understanding) “extends the allegorical treatment of the human condition in the direction of mysticism.”[7] Mankind presents the standard morality play sequence of innocence/fall/ redemption (in this play probably repentance) in less than an hour and a half.[8] Everyman begins with the prologue that states, “Here beginneth a treatise how the High Father of Heaven sendeth death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world and is in manner of a moral play.”[9] The theme of Everyman alludes to the parable of the talents in Matthew 25:14-30.

"Remy" as played by Judd Law in Repo Men

For those not wishing to see Repo Men [I don’t necessarily recommend it, but it fit the project here] The plot of Repo Men as summarized on IMDb: “In the future humans have extended and improved our lives through highly sophisticated and expensive mechanical organs created by a company called “The Union”. The dark side of these medical breakthroughs is that if you don’t pay your bill, “The Union” sends its highly skilled repo men to take back its property… with no concern for your comfort or survival. Former soldier Remy is one of the best organ repo men in the business. But when he suffers a cardiac failure on the job, he awakens to find himself fitted with the company’s top-of-the-line heart-replacement… as well as a hefty debt. But a side effect of the procedure is that his heart’s no longer in the job. When he can’t make the payments, The Union sends its toughest enforcer, Remy’s former partner Jake, to track him down.”[10]

The set of Repo men displayed similarities to sets in morality plays. First, the plot generated two distinct categories of people segregated by wealth. The plot, in a sense, moves from the Union company backdrop of wealth to the underground cityscape backdrop of poverty and need. Second, the majority of the movie took place at night. This provided a very dark atmosphere to the content of the movie. Third, displays of dead bodies throughout the movie along with the repeated death scenes provided a reminder similar to the open sepulcher in Everyman. Fourth, the movie drew the audience into the movie much in the same way as morality plays. The content related to present day culture that is fascinated by the marvels of the medical field. In the present culture, there is a surgery or a prescription for everything in today’s world. The movie also confronted the audience with the most basic desire, which is to continue to live at all cost.

Dance of Death, Paris 1486.

Death is a common character in morality plays. The character of has several important elements.[11] First, in a “dance of death,” death is portrayed as coaxing his victims to hop on the instrument of death, such as a spear. Second, iconography revealed that Death has multiple instruments from which to inflict fate on his victims. In many plays he is dramatized as “the dance of death.” In the “dance of death” Death, portrayed as a skeleton, plays his fiddle as Emperor and commoner move to his tune.[12] Williams explained that, “Sometimes a preacher pictures forth the horrors of death as the skeleton summons, one after another, sometimes as many as forty figures representing all conditions of man- and womankind. The Dance of Death has often been connected with the morality play.”[13]

There are two distinct scenes in Repo Men that suggest a dance of death. In the first scene, Jake and Remy encounter a docked ship that contained multiple people overdue organs. They enter the ship to repossess the organs and engage in a fight. The encounter looks like choreographed dance scenes with Remy and Jake fulfilling the role of Death.[14] The second scene in front of the pink door contained more similarities to the dance of death.[15] Jake and Beth must fight their way through several repo men waiting at the door to gain access. After killing three common guards, the repo men, eight in all, move toward Remy to face death by multiple instruments ranging from traditional weapons (knives and pistols) to common tools (hammer and hacksaw). This scene revealed several striking similarities. First, in the same way that the dance of death refered to people hopping on the spear, Remy’s victims hop on his tool of death, coming at him to receive their fate. Second, Death is depicted in these dances as having many weapons and so Remy employs several weapons in his dance.

Therefore, Repo Men displayed similarities to the morality play’s use of space, inviting the audience to become a part of the play through set arrangement and audience location. The movies as well as the sets of morality plays also reinforced the theme of innocence, fall, and redemption found in morality plays. The costumes reminded the audience of the vices or virtues through their elaborate design or their rustic hideousness. Through these tactics, the audience engaged the message of both the movie and the play, which intended to lead to self-evaluation. Next I want to look at plot similarities in Repo Men and Morality Plays.

[1] Arnold Williams, The Drama of Medieval England ([East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1961), 143.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Dorothy H. Brown, Christian Humanism in the Late English Morality Plays (Gainesville: Univ of Florida Pr, 1999), 97.

[4] Williams, The Drama of Medieval England, 172.

[5] Davidson, Visualizing the Moral Life: Medieval Iconography and the Macro Morality Plays, 124.

[6] Ibid., 47.

[7] Ibid., 10.

[8] Michael R. Kelley, Flamboyant Drama: A Study of the Castle of Perseverance, Mankind, and Wisdom (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979), 82.

[9] Vincent F. Hopper and Gerald B. Lahey, Medieval Mystery Plays: Abraham and Isaac, Noah’s Flood, the Second Shepherd’s Play; Morality Plays: The Castle of Perseverance, Everyman; and Interludes: Johan, the Husband, the Four Pp (Great Neck, N.Y.: Barron’s Educational Series, 1962), 196.

[10] “Repo Men” http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1053424/

[11] Sophie Oosterwijk, “Lessons in “Hopping”: The Dance of Death and the Chester Mystery Cycle,” Comparative Drama 36, no. 3 (2002): 263.

[12] Williams, The Drama of Medieval England, 147.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Sapochnik, “Repo Man,” 21:58-24:18.

[15] Ibid., 1:37:27-1:40:04.

Filed under Aesthetics, Gospel and Film, Philosophy, Spirituality, Theology

Superheroes and Society: What Batman and the X-Men Tell Us About Culture and About Ourselves

Here is an interesting article on cultural apologetics.

Check out Superheroes and Society: What Batman and the X-Men Tell Us About Culture and About Ourselves

Comments Off on Superheroes and Society: What Batman and the X-Men Tell Us About Culture and About Ourselves

Filed under Gospel and Film, Spirituality